beta luv jack

Realizing now that the newest issue is on the shelves (this one all about Chicago), perhaps I'm a tad late in mentioning that I wrote a piece for the Auteur issue of Stop Smiling Magazine about producer/ arranger/ soundtracker/ session man/ Rumpelstilskin/ pill-popper/ alchemist/ Angel of Death/ Oscar-winner all around genius Jack Nitzsche. A purt-sweet issue, that one, featuring pieces on Robert Altman, Terry Gilliam, and Nic Roeg, so if you still see copies, grab it.

While it's not my first piece, or my second, but my third piece on Jack, in its original form, it was perhaps my most ambitious piece to date. Unfortunately, the film script portions of it were excised for space, and so I figured I would post the original edition now, along with some soundtrack selections.

THE WORLD ON A STRING

Jack Nitzsche and his soundtracks

EXT. LANDSCAPE -- DUSK

Scene opens in wide shot of landscape, an expanse of America. Wheat ripples like gold. A lake is luminous in the background, reflecting the setting sun.

CUE WINEGLASSES RUBBED BY MOIST FINGER.

CUE INDIAN WHISTLE.

Strange, ephemeral, spectral sounds stir, ripple like the fields, the water, as if arising from the earth herself.

CUE NYLON STRING GUITAR AND INDIAN TOM- TOM.

A glint of light appears on the horizon: a will o’wisp? No, just the sun off a windshield.

CUE SINGING SAW.

A Studebaker crosses through the landscape shot, heading west. It traverses through what was once Indian land, the pale-faced pioneer trails cut and paved into black highway. The car rolls cross-country towards the promised land, its human cargo speeding toward destiny.

INT. OF STUDEBAKER -- DUSK

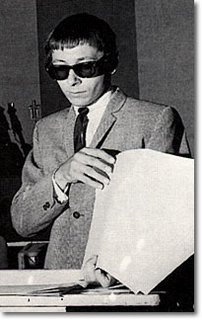

Cut to a man hunched over the steering wheel of the Studebaker. BERNARD ALFRED “JACK” NITZSCHE, age 19. JACK is scrawny, with thick black-plastic glasses and sheepdog bangs over his brow and ears. Pan over a backseat with all of his worldy possessions, including saxophone case from his nights honking R&B in smoky Muskegon, Michigan steel worker joints. A stack of sheet music reflects Jack’s correspondence homework for the Westlake College of Music out in Los Angeles, which is his final destination. As we watch, the wind flaps the stack free.

EXT. HIGHWAY -- CONTINUOUS

JACK’s sheet music flutters out over the highway, slowly settling on the landscape as the Studebaker plunges into the darkness ahead. Fade out.

Well, it could be a scene out of a movie, Jack Nitzsche’s life. How the first generation American, born to German immigrants (who dropped the “e” from their surnames to avoid comparison to their Zarathustrian-obsessed kin) was reared on his father’s opera and classical record collection, igniting a powerful addiction to music in the boy while he also excelled at piano, saxophone, and clarinet. Classical studies went out the window though when he heard the Penguins’s “Earth Angel” on the radio. Young Jack could hear what was hidden below: “It had death in it. Death is always a part of the music I make. Death means a lot.”

As did being a rebel. Stealing James Dean’s insouciant and sullen pose from Rebel Without a Cause, Jack headed to LA and quickly fell in with a foppish A&R man and songwriter Salvatore “Sonny” Bono, as well as madmen like Kim Fowley and Lee Hazlewood, before landing a role as arranger for the most rebellious and megalomaniacal of them all, Phil Spector.

INT. of GOLD STAR STUDIOS.

Recording session in full swing, twenty-one musicians jostling as the song is recorded.

CUE THE CRYSTALS “HE HIT ME (IT FELT LIKE A KISS).”

Jack ascended to become the main freemason of Spector’s Wall of Sound, erecting the mono-lith for him. He was the alchemist that could turn Phil’s every whim into notes on paper, scurrying to every lead sheet during sessions at Gold Star. That was the crucial element, gold, and Jack was Spector’s Rumpelstilskin, arranging “four guitars (to) play 8th notes; four pianos hit it when he says roll; the drum is on 2 and 4 on tom-toms, no snare, two sticks -heavy sticks- at least five percussionists” and spinning it so that the resulting single shimmered like that rarefied substance. It was not just din, but the sound of money flowing out of the speakers. When “Specs” (Phil’s nickname for him) was not being hired to dopplegang and replicate the sound of Spector for Doris Day, Bobby Darin, Jackie DeShannon, he ran with the nefarious Wrecking Crew and the Rolling Stones, England’s newest set of long-haired, blues-reared miscreants. The Queen of Beatniks, Judy Henske, recalls the chemical concoctions that fueled her recording sessions with Nitzsche: “We were both drinking (wine) heavily and were taking pills that were half Nembutal and half Desoxin…Desbutol. So, if drinking hadn’t made you crazy enough, the Desbutol would keep you awake so you could continue drinking.”

For the Stones (who he turned onto grass), Jack played piano. It was his ‘gypsy style’ on keys that helped them paint it black and he had the Stones ask of the shadows: “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby?” (which Jagger considered “the ultimate freakout”). The energy expended on their weeks-long recording sessions was revelatory to Nitzsche, as he realized that such force could be focused in the recording so as to alter consciousness through pop music. Arranging and commingling the teen music of Chuck Berry, Marvin Gaye, James Brown, the Supremes, the Stones into a commercial behemoth for The T.A.M.I. Show; turning Monkees’ chirps into porpoise songs; making Marianne Faithfull into Sister Morphine fulltime; Jack’s unseen hand is there, alchemically transforming sound, in (Marianne’s words) “an attempt to make high art out of a pop song.”

He did the same for the only member of Buffalo Springfield that he gave a flying fuck about, Neil Young. Jack believed in the songs, that the shaky singer could stand solo, and so he made that epileptic Canuck hold steady at the edge of an eagle feather.

CUE BUFFALO SPRINGFIELD’s “EXPECTING TO FLY.”

He swaddled Neil with the aurally-hallucinated soar of flight, aiming him towards an effervescent choir of brown-eyed nymphettes, the listener ultimately far from heaven. He would later overdose Neil on the London Symphony Orchestra’s strings on Harvest, much like he did to the Stones on choirs and French horns on “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” Such opulence opened portals though, and as pop and rock’n roll divulged all of its mysteries over the course of the decade, Nitzsche dabbled deeper in musical magic, entering his next career phase: soundtracks.

INT. OF CRAMPED ROOM. -- MIDNIGHT

Very dark, cluttered, only vague shapes of bizarre frightening statuettes and masques can be made out. Smoke enshrouds everything. Close-up as JACK inhales cocaine off of knife-tip. He laughs wickedly, leans back over his lead sheets. From his neck dangles a locket taken off a voodoo woman’s tomb.

CUE BLIND WILLIE JOHNSON’S “DARK WAS THE NIGHT.”

Contracted to score Donald Cammell (Aleister Crowley’s godson) and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance, Nitzsche concocted the soundtrack while ensconced in a witch’s cottage down in Laurel Canyon. Fueled by Cammell’s coke, possessed by malevolent spirits and in possession of a prototype device called a synthesizer, Jack rooted deep, invoking crossroad blues, sitar-trance states, sinister sinewaves, voodoo drums, and wails of ritualistic sacrifice for the soundtrack. Nitzsche’s cauldron bubbled as he brewed it all together; call it goat’s head soup. “I was trying to capture the effect of taking one breath in and letting two breaths out.” Such hyperventilating exacerbated the synesthesia of the film and the dark world portrayed on celluloid carried beyond the frame: Jagger embodied the vile role of Turner full-time, fucking Keith’s girl and co-star, Anita Pallenberg. She swore off of movies forever afterwards. Star James Fox turned to Christ to save his soul. Nitzsche’s powers were crescent.

The schizophrenia of LSO strings on his disorienting St. Giles’ Cripplegate (from 1972), became Jack’s calling card. Even Bernard Hermann dug it, and it secured him the gig scoring One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Again, strings convey a psychologically precarious state, where the mentally unstable are dosed with staggering amounts of pharmaceuticals (a condition Jack knew recreationally). Loopy, spongy waltzes maintain the placid status quo of Nurse Ratched. Woozy, staggering slippery motifs are arranged for wineglass, singing saw, dobro, fiddle, Indian drums. Brilliantly dazed, regal in its madness, Nitzsche’s score missed out on Cuckoo’s Academy swoop, losing out to John Williams’s cello undertow from Jaws.

Jack’s next big project was William Friedkin’s The Exorcist. Though it had demonic possession as its theme, the split pea spew and crucifix humping held significantly less darkness for Jack than Performance. Mad with demons during the latter movie, for The Exorcist, it was just a job. With a wave of the wand, a counterclockwise motion on crystal chalice, he delivered what original composer Lalo Schifrin failed to give, the aural effect “like a cold hand on the back of the neck,” as Friedkin put it.

Jack was up to his neck beard in darkness, though. Living out at Neil Young’s Broken Arrow Ranch, he would drink to the brink of madness, grind his hands into smashed glass for kicks, tell his son Jack Jr. that he himself was “the Angel of Death.” Every substance at hand was mixed together in his bloodstream. He was the last living soul to speak to Crazy Horse bandmate Danny Whitten before his valium overdose, and in a limousine with Gram Parsons on the Time Fades Away tour, Jack presaged his fate: “You look like Danny…and Danny’s dead.”

He also wound up shacking with a woman he despised, Young’s ex-wife, Carrie Snodgrass. Coming to her house with both pistol and head full of gunpowder one night in late June, 1979, he found her in bed with another man. Foggy though the subsequent details were, Jack soon found himself facing five criminal charges, the most lurid being “rape by instrumentality.”

The Hollywood Babylon-esque debacle and debt eventually cleared, and Jack finally lifted an Oscar for Best Song, Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes’s “Up Where We Belong” from 1982’s An Officer and a Gentleman. Boilerplate though it may sound (producer Don Simpson hated the tune), it was the culmination of Jack’s singer-songwriter side; sentimental, sappy, yet soaring, hailing the great spirit of the eagle in song. It marked a return to the top of the charts, to a peak not glimpsed since his days with Spector.

That gold statuette was but a false idol. Getting into an entanglement with some young punks who swiped his hat, Jack flashed that pistol once more, and his last public appearance was in an old episode of COPS. Hogtied in the middle of Hollywood Boulevard, Jack impotently summons his new, feeble god.

EXT-HOLLYWOOD BLVD.

ARRESTING OFFICER pushes at a handcuffed JACK.

OFFICER: “Keep moving, Academy Award winner.”

CUE CLOSING THEME.

FADE TO BLACK.

Extended Play:

Captain Beefheat - "Hard Working Man" from Blue Collar

Jack Nitzsche "Miryea" "Whorehouse & Healing" from Revenge

Jack Nitzsche "The Razor's Edge Suite" from The Razor's Edge

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home