heep see

Robert Altman

Secret Honor

Tanner '88

Used to the ensemble sprawl and clamor of Nashville, M*A*S*H, The Player, and Short Cuts, the smallness of these is almost shocking. Downsizing in the 80s? There's these little details: the quick, overheard asides like "What television can't cover is change"; how a joke unfolds in the mirrored shades of a Secret Service detail as they clean their guns. Altman's work with Garry Trudeau dovetails nicely, the mental comic strip boxes still intact inside what Trudeau notes is Altman's "cubist sensibility."

Nicholas Roeg

Performance

Bad Timing

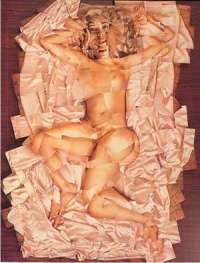

Eureka

Re-watching Performance reveals scads more info each go, but still remains truly wtf? in its haltingly early attempts to portray schizophrenia and LSD-induced loss of identity. I'm a sucker for such films (Bergman's Persona and Altman's desert-delirious 3 Women spring to mind at present). It's clumsy at times as the language isn't necessarily there just yet, but by Bad Timing, Roeg melds his characters together deftly to where fleshy boundaries disentegrate as they really do appear to be a three-sided identity (or, as you cannot quite tell each character's impetus, it kaleidoscopes into something six-sided), rather than just being Art Garfunkel, Theresa Russell, and Harvey Keitel. The jumpcuts are those of a master, awash in vibrant colors (in Vienna, no less) the movement of bodies and hues as rhythmic and as graceful as any modern ballet.

Eureka is more troublesome, more lugubrious and weighty. While allusions to Klimt and Billie Holiday in Timing are subtle, the Qabbalic underpinnings in Eureka are heavy-handed. Right, Rutger Hauer happens to have on a shirt with the Tree of Life stitched into it, and then there's the Tarot card that Gene Hackman draws of the Hanged Man, its prophecy echoed when his burned corpse photo is hung up at the trial, the angle nearly upside-down. But Roeg is usually more nuanced than this.

Jafar Panahi

The Mirror

Abbas Kiarostami

Ten

Condi's head talking about the nuclear negotations with Iran; an NY Post political cartoon staking its claim that they know where the WMDs are, past the dotted Iraq line towards a mushroom cloud labeled 'Iran'; the game already afoot. But what do they see in Iran? Kiarostami is perhaps most well-known, but both men are working within stringent parameters here. And the viewer is taken along for the ride, literally. Amid the maze of streets in Tehran in these two films, the camerawork is really claustrophobic, trapped in a car in traffic, stuck on either the woman driver or any number of her passengers and the agitated conversations they have, touching often upon the plight of women in the country. Simple, and yet I can't help but feeling that there is far more brimming under the surface of each film, allegories so immersed under layers so as to escape the notice of censors and all but the most-attuned.

The Mirror is similarly focused (not surprisingly, since both gents work together) with Panahi's camera handheld, almost Cassavetes-like in its clandestine coverage of street scenes, the beginning of the movie scanning the little schoolgirl, moving along at her eye level. Viewers are as perplexed and lost amid the urban din as she is; almost all of the adults are out of our viewline right around their shoulders, similarly calloused and faceless to her plight and struggle to go home. Tracking shots continually lose her behind the broadsides of passing trucks and buses. Some 38 minutes in, it all breaks apart, as the movie bursts outside of its own framing, just as life always does.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home