beta feels old, ham, joy

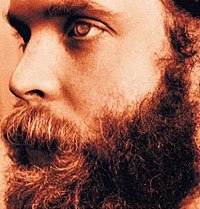

Every moment that Will Oldham is on the screen in Kelly Reichhardt's second feature film, Old Joy, it's impossible to look away from the man's mesmerizing, almost-freakish visage. Playing the perpetually-stoned and non-commital Kurt, that expansive pate, protruding forehead, and thick jut of amber beard threatens to overtake the film's surroundings, and yet the film's main focus, Mark (played by Daniel London) more than holds his own with his own intent stare.

Every moment that Will Oldham is on the screen in Kelly Reichhardt's second feature film, Old Joy, it's impossible to look away from the man's mesmerizing, almost-freakish visage. Playing the perpetually-stoned and non-commital Kurt, that expansive pate, protruding forehead, and thick jut of amber beard threatens to overtake the film's surroundings, and yet the film's main focus, Mark (played by Daniel London) more than holds his own with his own intent stare. His eyes are closed when the film opens, as he practices his meditation despite the blender of his pregnant wife and the phone call of his old friend. Mark is trying to do good in the world, trying to set it to rights as he drives his Volvo, listening to ranting left-wing talk shows, trying to remain centered. Or has he divulges at one point: "Find another rhythm, do what other people do."

The film, based on a short story by Jonathan Raymond and expanded to a full-length with Reichardt, is simple enough in premise: two friends decide to reconnect for a quick camping trip before paternal duties tear them asunder for good. They smoke a jay, get bummed about a record store they once knew and frequented closing down, feel the highs of the past come much lower now, and guards remain raised. And yet no interaction between two people, be they lovers, friends, or strangers, is ever that simple. Every word echoes an unseen past.

As the last post's faceless dialogue attests, Will Oldham himself, his creak of mystery, his crackled voicing of the unknowable ancients, resonates deep within my roots. Hearing him, seeing him, moves me to a heady time of my life, to malleable, infinite-possibilities of young years, to invincibility, to you know, the "quiet joys of brotherhood." So to see him portraying an old acquaintance makes me re-think my other strained and fissured-with-time relationships to friends in the past.

Throughout the quiet --at times unspoken-- dialogue between the two old friends, I project myself and my estranged friendships instead, toggling between which man perhaps represents us best. Am I more the ever-adrift and dispersive Kurt or the self-immolated tethering of Mark? Am I lost amid devilish details or else on the road to hell paved smooth with good intentions? As the men make u-turns, get lost, seek drunken shelter from the encroaching darkness of both Oregon rainstorms and inpenetrable forest dark (cinematographer Peter Sillen captures the overcast skies, the umbrage and chill of trees come evening exquisitely) or else wander slowly along faint trails towards their destination, there is the small realization of no straight trajectories, no cut and easy path to travel. "It is to be on one thing only, on the road to God knows where," Kurt croaked in another life.

The film's center, soaking in the buck in cloistered hot springs with a can of Hamm's to cool them, is silent, just the gurgle of water and steam rising between pale feet. His hands move to Mark and yet there is no resolution. As the discussion afterwards goes, Reichardt wonders about idealism when it is unforgiving or unable to come across and reconnect, to forgive with grace. Grace...that's an unwieldy word. I still find myself in such a limbo, wondering (with a line that echoes one once written to me in a long-buried letter) if the wires can ever be burned clean, if there is ever true connection between people. Is communion only in the past?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home